Bilingual schools

Elementary school programs give students advantage of biliterate education

January 4, 2019

Photo by Holland Rainwater

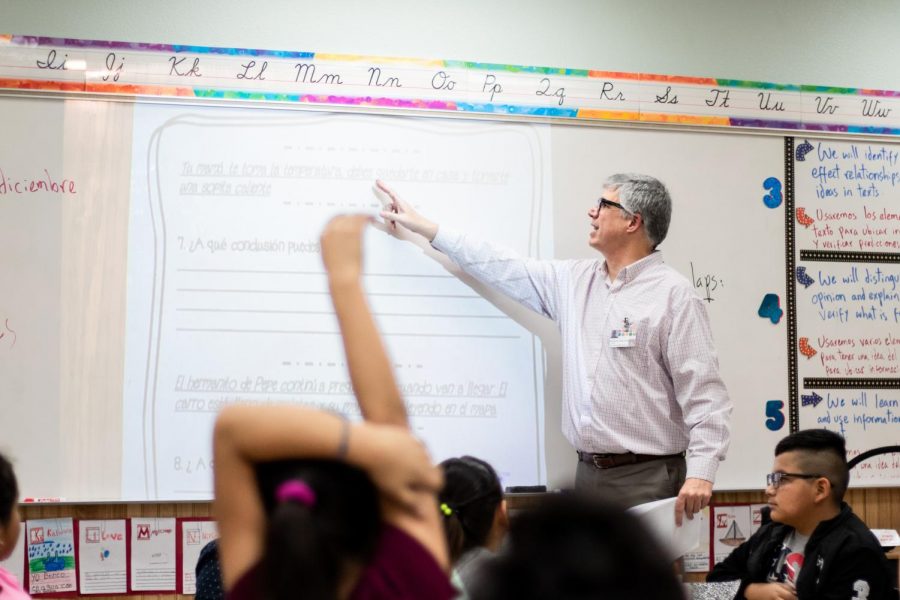

Students of Nash elementary raise their hands to answer a question on their assignment. Bilingual teacher teaches a class completely in Spanish. Depending on the day, the class alternates between languages that the class will be taught in that day.

Words fumble around the mouths of children as they try to string them together into a sentence. Their tongues twist and turn as they try to pronounce sounds foreign to them. Their thought processes are hindered by their vocabulary and ability to build sentences, and communicating is nearly impossible.

That’s the issue that bilingual programs are aimed to fix: to bridge the gap between the native language and English. Nash Elementary and Highland Park Elementary have bilingual classes in which students are taught in both English and Spanish.

“The bilingual program in TISD began in 2008-2009. At that time, TISD was responding to a growing population, after having 119 district-wide English learners the year before,” Coordinator of Multilingual Education Mindy Basurto said. “Our English learner students were largely Spanish-speaking as they largely are now; therefore, we offered a Spanish bilingual program.”

In terms of teaching this new generation of bilingual students, both elementary schools follow what is known as the Gomez and Gomez Dual Language Enrichment Model.

“It’s designed to where Monday, Wednesday, Friday are Spanish days, and Tuesday and Thursday are English days,” Nash assistant principal Liliana Luna said. “But as far as instruction goes, when you’re in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade, you’re reading and writing is always in Spanish because we want to develop that native language. And then starting in second grade, you get both in English and in Spanish. The kids transition from all Spanish to English really well.”

Along with the teaching method comes the difficulty of attracting qualified teachers to the area.

“It’s been difficult,” Luna said. “Because we’re in less of an urban area, we don’t attract a lot of bilingual professionals. So when we do have an opening, we are required to look outside of our school.”

Luna said they have traveled to the international job fair in Houston seeking applicants.

“Sometimes it is difficult to convince people to come work in small Texarkana,” Luna said. “We have people that will come, but then they realize this is not the type of town that they really were thinking and end up moving.”

Ultimately, they hope that, as the program grows, they will be able to encourage high school students to pursue teaching degrees and return to the district to work.

Although the two elementary schools seem all-encompassing when it comes to the bilingual students, it was not long ago when TISD didn’t have a bilingual program.

“We didn’t start pre-K through fifth [grade]. We just started with pre-K through kindergarten, and then we added second and first grade and so on,” Highland Park principal Jennifer Cross said. “As those kids moved up, we kind of just increased at one year at a time.”

Bilingual education hasn’t escaped controversy. Critics state that since English is the most widely spoken language in the world, there is no need for young students to be burdened with a second language in their education. However, Cross holds a different view.

“I think [being bilingual] is important, and I’m almost envious that I am not bilingual,” Cross said. “And just because they speak a native language doesn’t make them more or less entitled to learn English. So if they can become biliterate, which is having that academic language in Spanish as well as English, they will be three steps ahead of everybody else. It’s awesome.”

Even though many would expect criticism from outside the bilingual community, both school districts face difficulties with educating the parents of the bilingual students as well.

“There’s a little bit of a struggle with the parents in that the parents want that English acquisition quicker than [at the rate] they’re getting it,” Cross said. “But we constantly try to reiterate to parents that it’s important to get that knowledge in your first language, and then it’s going to translate very easily into English.”

Aside from outside criticism, the district faces a bigger problem: class sizes. Forty-two percent of Nash students don’t live in that attendance zone.

“When I first started here eight years ago, we were at 400 and something. Now we’re close to 700,” Luna said. “[There’s a] large population of transfer students who do not live in the area [who] are choosing to come here, and a lot of the transfers are within [the bilingual] program.”

These exceedingly large class sizes have led to many bilingual students from the Highland Park area to be bused to Nash in order to go to school. I

“However, if the student lives across town and there is no space at the closest bilingual campus, we will transport students to the campus that does have space available,” Basurto said.

Bilingual programs have been shown to be effective in creating students who are bilingual, bicultural and biliterate, which is a district goal, Basurto said.

“Reading scores for students who are placed in dual-language bilingual programs far surpass those of students who are in ESL programs, so we strongly encourage families to consider the dual-language bilingual program we provide to our English learners who are Spanish speaking,” Basurto said. “Once a student learns to read in the first language, all of the literacy skills transfer to their second language. A student’s successful literacy acquisition in both their first and second language is directly related to phonological awareness in the native language. This is why we are bound by law and by ethical obligations to provide our students with the best opportunity to help each individual student succeed.”

Due to the large class sizes and the increased need for transportation, the district spends more money on these students, although federal and state funds cover these extra costs.

“Our district receives federal and state funds to help us educate English learners,” Basurto said. “Our state bilingual allotment is a little over $240,000, and our federal Title III funds are a little over $46,000. These funds must be used for specific things that English learners need in order to attain English proficiency and to access the curriculum.”

Despite any difficulties faced by both schools, they still hold firm beliefs that they are helping these children and giving them an advantage. Students who are in the bilingual program should graduate not only speaking the language but being able to read it and write it.

“Depending on what career field they go into, being biliterate is definitely going to give them an advantage,” Luna said. “It has been an advantage for me. I feel like it has helped me advance within my career because I am bilingual, or biliterate, and TISD offers what they call a bilingual stipend, that’s additional money for employees who are biliterate.”

When it comes to getting a job, being bilingual may put one applicant over another.

“If you have the same level of education, same level of experience, but one [applicant] is bilingual and one isn’t, it’s definitely going to be an advantage,” Basurto said. “So that, I believe, is a huge benefit.”