Bending to a puppeteer

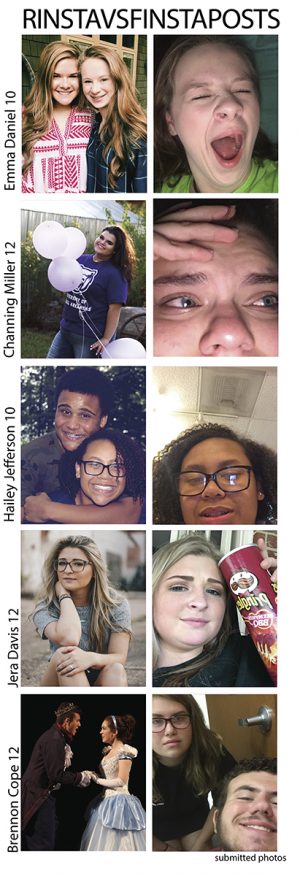

High standards of social media lead some teens to create a 'finsta' in addition to a 'rinsta'

November 3, 2017

She is graceful, dancing on light feet with confidence. Click. She is beautiful, every girl’s dream image. Click. She is effortless, happy, but her movements are not her own. They are manipulated, forced upon her by a masterful puppeteer, done only to please a stubborn audience–to please the world.

Invisible strings are attached to every camera’s click, composing a story on the screen. The strings direct glistening smiles, flawless makeup and countless filters to make a picturesque profile of a perfect person. But once detached from the strings, there is a story less heard. One of smeared makeup and tough breakups, failed tests and bad days; one that demands an audience.

For many students, this relief from the tyrannical on-screen pressure comes in the form of a “finsta,” or fake Instagram, made in addition to one’s real Instagram account.

“It’s a place where I know I can post as much as I want and post whatever I want,” senior Channing Miller said. “Only the people that I want to see [my posts] will be able to.”

Finsta posts have no limitations. They are not constricted by the taut, oppressive wires which regulate the feeds on their accounts they broadcast to the public. Finsta posts may range from memes to memories, depression to dog pictures, but ultimately finstas are a place for students to be free from normal, unsaid, but understood online restrictions.

“The basic rules and regulations of Instagram are: post only happy or positive things like you and your friends, or you if you accomplished something or the dress up days at school,” Miller said. “Don’t post, ‘I’ve had a bad day.’ Don’t let people see there’s a bottom side to you that’s not-so-great.”

Main Instagram accounts, or “rinstas,” are regulated by these unspoken rules that filter their posts and control their decisions like a puppeteer with a marionette.

“Real instagram is kind of like the Photoshop of my life,” senior Brennon Cope said. “It’s mostly snapshots of really good moments. Finsta takes it a step further because not only could it be the really good moments, like starting a new relationship, but it could also be the really sad moments, like a break up, or angry moments, like failing a test that you need to get off your chest.”

These communities sometimes act as a support group of sorts to students.

“It’s more of a myself thing. I don’t really care if other people see it. It never actually occurs to me that other people see it,” Cope said. “I just kind of feel like if I say it out loud and it’s recognized by at least one person, then it’s a load off of me. It lets me get it off my chest. I don’t want to spam my real Instagram with all that nonsense I have.”

However, while it may seem beneficial to adolescents to use these private accounts as an outlet for emotion, they often times may not truly consider the aftermath of their venting. It is easy to cross boundaries when there seem to be none regulating one’s actions.

“Social media allows teens to put very personal information out to masses of people about themselves or about others that should remain private,” licensed professional therapist Jennifer Aslin said. “I think a lot of teens and even adults are no longer good judges of what should be public information and what should be private information.”

The selectivity users show in who they let follow them varies from person to person. Each person must decide who is permitted to join their inner circle and who they trust to keep their place of refuge intact. This process is completely subjective and if not taken seriously could be disastrous for their reputation which they obviously so desire to uphold.

“Typically, if I don’t know the person, I don’t let them follow me. If I feel like the person is going to take what I post and run with it like, ‘Oh did you see what so and so put on their finsta?’ ‘Omg I can’t believe she posted this!’ ‘She’s such a child for posting this; she’s just overreacting,” Miller said. “I ask: ‘Does this person really care about me and understand what I’m going through, or are they going to run up to people and say, ‘Wow, Channing posted about being upset. I can’t believe she’s dramatic.’”

However, people often times don’t take into careful consideration that relationships sometimes go awry, and if one is permitted into the gates of their private accounts, a single screenshot could destroy their safe haven. Since most finstas are private, users automatically assume it is not public information.

“If a student is looking for a support group, it is best to find one that they can participate in face to face. Maybe this is a close group of friends, a support group, or parents and family members. Real cries for help can be dismissed or minimized or even completely misinterpreted as an attempt to get attention when they are put out on social media,” Aslin said. “This allows for some accountability, cuts down on false information being put out there, gives opportunity for reality testing and the ability to learn useful coping skills and gives a person a visible support system they can rely on.”

The importance of face-to-face contact in today’s society has slowly deteriorated as people have become more reliant on communication through social media. It is not a secret. Social media is a crucial part of so many lives, laced and intertwined in everyday interactions. People bend to the will of social media–a rag doll, limp and submissive.

“Everything’s become surface-level. I think our generation is very judgmental as far as appearance goes,” Miller said. “The way you dress, if you’re a girl, if you wear makeup or not, and how well it’s done, if you’re a boy, then the way you do your hair. I feel like before social media was a big part of our lives, it wasn’t such a thing that you could judge them early on, you had to be there face to face and talk to them, and you would get a better understanding of a person.”

People are judged by how many followers they have and how many likes they get, rather than the measure of their character. It has become it’s own, more acceptable form of social hierarchy.

“Having more likes gives you a feeling of satisfaction,” senior Jera Davis said. “You have the sense, whether it’s true or not, that people care about you.”

Real accounts, as pleasing as they may look to the eye, fall short of reality. It is a place to boast without directly boasting. A place to broadcast the image you want to broadcast–a false reality. This is ironic considering one’s fake Instagram is more truthful than their real one.

“I think people like to live in a sense of false reality where nothing bad happens,” Miller said. “I feel like I’m more to my true self on my finsta because I have my full range of emotions. On my real insta I’m never like ‘I hate myself,’ but on my finsta I can be like ‘You know, today I had a really bad day. It seems like things aren’t really looking up,’ things that I wouldn’t want everyone to know.”

The mere need for existence of a finsta proves that social media is too restrictive. It proves that people are desperate for a confidant for their emotions and secrets, and by cutting the strings that bind them to a false identity and being themselves, they can develop honest and meaningful friendships showing that finstas, as ridiculous as they may seem, can have a positive impact.

“Sometimes your friends aren’t always there to listen, and sometimes the people you think are going to listen to you don’t,” Miller said. “For example Molly Crouch, a former senior, came back from college over the summer and she and I went and got snow cones and talked for like three hours, and we’ve had hour long conversations over Snapchat. That never would have happened if I hadn’t made a finsta. Sometimes she’s there for me more than my closer friends are.”