Graphic by Anna Grace Jones

Matters of the heart

Instances of sudden cardiac death spark debate over effectiveness of physicals

February 13, 2020

It can hit anytime. It can hit in the first minute of practice. It can hit at the first play of the game. It can hit going into the locker room. It can hit away from the school, away from the field or court when there’s nobody there to respond.

Sudden Cardiac Arrest (SCA) is an electrical malfunction within the heart that often results in death. Annually, SCA causes the deaths of over 2,000 children and adolescents in the United States. Immediate and drastic symptoms of SCA include sudden collapse, lack of pulse and breathing and a loss of consciousness. Without immediate action, only 10% survive.

“The bottom line is they don’t give you much warning,” said Dr. Mike Finley, chief medical officer for CHRISTUS St. Michael Health System. “It’s very sudden. It’s very unpredictable.”

Despite the rarity of these conditions, three students have died from heart-related issues in the past three years–Leonard Parks in 2017, Dee Lewis in 2018 and Damian Coats in 2019. All three were physically active black males, two played on the football team.

Each one died suddenly, leaving a hole in the lives of their family and friends and a community asking if there was a way their deaths could have been avoided.

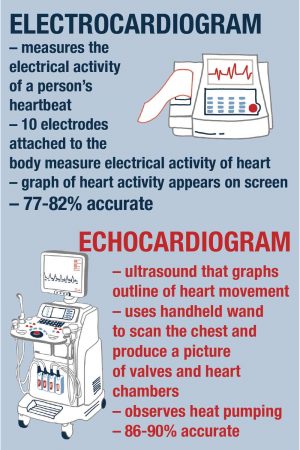

Detecting conditions that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest is often difficult. A combination of blood tests, electrocardiograms (EKG) and echocardiograms are the most common tests used. However, these are not part of the routine physical exams for student athletes.

“You’ll see that there are about 30 million sports physicals done every year in this country, and they are woefully inadequate to spot the extremely rare person that has a problem,” Finley said.

An EKG is a test done on the heart that measures the electrical pulses of the heartbeat. Although the test is an improvement from prior techniques, it is not a catch-all method. There have been multiple attempts to try to find what Finley calls the “golden nugget,” the solution to effectively identify heart irregularities.

“A good physical exam is limited when you’re doing sports physicals because, typically, they’re done on one evening, and you line up literally hundreds of teenagers,” Finely said. “They’ve talked about doing [electrocardiograms]. They’ve talked about doing ultrasounds of the heart called echocardiograms. They’ve even talked about doing stress tests. And none of those have panned out. These are so rare that you would have to screen so many people.”

Even with these tests, Finley said catching abnormalities is not 100%.

“Sometimes [abnormalities] are very subtle,” Finley said. “When you’re looking at 300 or 400 student athletes in line coming in, you just hope that you pick out the one, maybe two, that need a little something else done.”

As heart abnormalities become a more pressing issue in the realm of student health, there is a movement to include EKGs and echos as regular components of student physicals. However, feasibility and cost are a concern.

“The cost is astronomical when you add it all up,” Finley said. “If you have a family member that has one of these sudden deaths, you wouldn’t mind what the cost was, but in order to pick one of these up, there’s nothing that shows that it’s predictable and cost effective.”

To perform a screening with an EKG and echo on all student athletes during physicals would be difficult to do, Finely said, and requiring them go to a doctor or outpatient facility would cost several hundred dollars per person.

“It would be a stretch for a school system, or even a family, to afford that,” Finley said. “Some families have three or four kids doing these.”

In order to make it feasible, Finley suggested finding donors to offset the cost.

“I wish I had a great answer for this,” Finley said. “If we were going to do this in this community, for example, I would recommend that we have a campaign and that we have support from donors that would want to be involved in this and get the right thing done in the most efficient and the most cost efficient way.”

The Cody Stephens Go Big or Go Home Foundation is a Texas nonprofit organization that helps schools perform EKG testing for all student athletes. The organization was founded in memory of Cody Stephens, a Crosby High School senior and football player who died in 2012 from sudden cardiac arrest.

“We lost Cody right before he graduated from high school,” Cody’s father Scott Stephens said. “He was getting ready to go play college football. He was a 6’9”, 290-pound kid that had the world by the tail. There was no indication, that we recognized, of any kind of heart abnormality that might lead to sudden cardiac arrest.”

Stephens said he wished that EKG screenings had been part of athletic physicals when Cody was alive.

“The current sports physicals are wonderful tools,” Stephens said. “They have been in place for a lot of years, but they really haven’t progressed. Cody had probably basically the same physical that I had in 1978. We’ve made a lot of medical advances over the course of 40 years, yet, we haven’t really applied it to our physicals.”

According to Stephens, adding an EKG test to sports physicals increases the likelihood of detecting heart abnormalities that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest from 3% to 86%.

“I wish it was a perfect test,” Stephens said. “I wish it caught them all, but it’s not ever going to catch them all. We’re coming up on 170,000 kids that we’ve screened since my son passed away. We’ve found that about one out of 900 needs some sort of medical intervention, heart surgery or medication. They don’t know it, but their lives can be saved.”

Following Cody’s death, the foundation lobbied for the passage of House Bill 76, also known as Cody’s Law, which requires high schools to distribute information about sudden cardiac death and the opportunity to request an EKG screening as part of the University Interscholastic League (UIL) standard physical. The law went into effect Sept. 1, 2019.

“Everybody, by law, has to implement [House Bill 76] this school year,” athletic director Gerry Stanford said. “So everybody has to print and send out [the UIL form] that goes out into the athletic packet that every kid gets from entering seventh grade all the way through entering 12th.”

In an email from UIL Deputy Director Jamey Harrison, school athletic departments were informed of a change to the Pre-Participation Physical Examination form that includes a section where parents can check “yes” that they would like EKG testing.

According to the email, “the law does NOT require schools to begin offering EKG screenings. Additionally, schools are NOT required to pay for or arrange cardiac screenings for students who check the ‘yes’ box on the PPE form.”

Though a parent may check yes to request an EKG, students may still be cleared to participate in athletics unless a district policy says otherwise.

“As long as the student would be able to participate based on the answers to the questions on the Medical History form, the student may participate,” the email states. “The student and his/her family are responsible for having the ECG conducted and read. Schools MAY assist in this process and MAY provide cardiac screening opportunities. Schools are NOT required to do so.”

Although TISD has not created any new policies, Stanford said the athletic department is looking at their options.

“We will continue to meet with our team doctors and trainers to formulate a plan that is in the best interest for all of our students,” Stanford said.

With that in mind, the Cody Stephens Foundation attempts to make the EKG testing cost efficient and readily available for schools.

“Our policy is that if your school district has never screened before, we come in the first year and screen anyone that is required to have a student physical, and we’ll do that for free,” Stephens said. “And then we ask that you find a way to continue the program for the next year. [At that point], it’s at a cost of $20 which helps us sustain the program to go to other places and do it for free.”

While cost varies widely, the average cost of an EKG without a partnership with a program can be up to $50 a person, and it can be up to $175 for additional exercise stress tests. With the partnership, at least some of the burden of paying for their child’s safety is alleviated from parents.

“It’s a big state. Obviously, resources are limited, and we can’t do it for free forever,” Stephens said. “But we want to give it away the first year and show that it works and how easy it is.”

Indicating on the medical history form if there have been any signs or symptoms related to cardiac problems is the first step in diagnosing heart conditions.

“We have kids who get [diagnosed] through our physical tests,” Stanford said. “They end up with some type of heart doctor or their own doctor that can do these things.”

Even with improved testing, there is no guarantee to catch every problem, and there is the issue with accuracy.

“EKGs don’t solve the problem. They just give you some clarity, but don’t give you the answers. There’s plenty of history that shows how many false positives come out of an EKG that create a lot of problems,” Stanford said. “Obviously, there is also another percentage that shows where an EKG can catch certain things.”

Science teacher Kelly Rowland, who also serves as the Miller County Deputy Coroner, said cardiac testing should be a required component of athletic physicals.

“We expect our athletes to push themselves to the brink, as far as they can go, to athletic physicality,” Rowland said. “If you have an underlying cardiac issue, that’s when you’re going to see a problem with that, and I think that it’s super important that if we expect them to go to those extremes that we make sure they can do so safely.”

Even though EKG testing may result in false positives, many regard having more advanced testing as safer than not.

“I’m not a doctor, but I do think there are some tests that they could do that are not terribly expensive or invasive that would give us an idea of their hearts performance under stress,” Rowland said. “I do know that there are always going to be some conditions that won’t be able to be detected by testing, but if we could pick up on just one or a few that would be better than missing them.”

According to Rowland, the boundaries student athletes are expected to push call for an even greater emphasis on health.

“There needs to be a way to make sure that every athlete that is asked to push themselves to their limits is taken care of and protected,” Rowland said.

Testing alone, however, cannot completely protect an athlete. Athletes must also, in Rowland’s opinion, take it upon themselves to be at the forefront of their health.

“Yes, [heart conditions are] rare. How rare is it for a teenager to not treat their bodies with the best respect that they can? That’s not so rare,” Rowland said. “Some of the teens that are doing athletics are consuming some substances that push their cardiac system beyond its limits. Some of the sports drinks, the energy drinks, some of the substance abuse that we see, they do strain the cardiac system, along with other body systems.”

Sports industries have made advancements in the past, whether concussion protocol or preventing overheating and dehydration, when issues have affected large groups of people. The rarity of heart conditions, though, has often led to their under representation.

“Do I think it needs attention? It needs attention if it’s just one student. And we’ve seen already it applies to way more than one student,” Rowland said. “So, the fact that it’s not hundreds or thousands of students is a little bit irrelevant, because if it just applies to one or a few it’s important to make sure that it’s checked.”