Born in the USA

January 4, 2019

In recent years, immigration laws have been toyed with as our leaders decide what is best for the well being of our country. This controversial topic has formed uncertainty in regards to navigating in a nation heavily merged with immigrants. The legality of granting citizenship to illegal immigrants, despite their difficult circumstances, has been questioned. In order to compensate for the success of all students, bilingual programs have been incorporated into elementary schools, hoping to bridge the gap between Spanish and English speaking students. Every day our country aims to manage this complex issue so that one day this tension will be erased.

Proposals and policies

Presidential announcement causes fear for immigrants

A threat. Not a plan. Not a block. Not a wall. A threat that sends millions of families into dismay. The idea of deportation, loss of citizenship, or separation of family are implications that would shake any person to the core, but for so many who reside on United States land, this is the reality, this is the fear.

Since the beginning of President Donald Trump’s campaign in 2015, immigration has become a top grossing political topic and increasingly controversial as it climbs. He aimed to restrict illegal immigration through executive orders and the proposed wall along the southern border, and has kept this as a key topic during his term. This sparks tension between opposing parties and has opened the door for a new conversation regarding immigration.

“An executive order is a way the president can get around Congress and be able to say, ‘I have the authority to do this thing. I don’t need congressional approval to do it. So I’m putting the order in place,’” AP United States History teacher Chuck Zach said. “When somebody is unhappy with the order and wants to challenge it, they can take it to court and say he doesn’t have the authority to do that, or his order in some way, violates the Constitution.”

In October, Trump announced his proposal of an executive order to essentially deny birthright citizenship to people born in the United States but of illegal parents. Some view this as undermining the 14th Amendment of the Constitution. Section One of this amendment ensures citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

“Well, migrants or immigrants have certain push and pull factors that either force them to leave their homeland or attract them to a new place,” United States History teacher Lance Kyles said. “Being a citizen with all the rights included in United States citizenship is a pull factor that would attract people to come and try to have a child here. [Trump] wants to remove that reward [by passing the executive order].”

The argument for this order is that the children of illegal immigrants should not be granted citizenship because they are not born of parents legally under the jurisdiction of the United States.

“The 14th Amendment goes under the premise of somebody that’s born in the United States or naturalized as a citizen automatically,” Zach said. “The president is looking at it and saying, ‘Well, [immigrant parents] came into the country illegally, so if the parents came in illegally, and the [children] were then born in the United States to parents of illegal immigrants, that doesn’t give them legal citizenship.’ That’s the way he’s looking at it.”

If Trump’s executive order is passed, it is safe to assume that it will be challenged in Supreme Court on the grounds that it goes against the Constitution. The judicial branch has jurisdiction over constitutional interpretation, so the proposition of this order taking power from the Supreme Court will likely spark tensions.

“The Supreme Court is the law of the land. Those are the nine most powerful people in the United States of America because when people ask, ‘What does this law mean?’ It means what they say it means,” AP Government teacher Hunter Davis said. “There are a lot of court cases that have built precedents long after the constitution that incorporated that concept of citizenship into the 14th Amendment [by the Supreme Court].”

This is not the first instance where Trump has threatened to pass an executive order to discourage illegal immigration. In Jan. 2017, he issued one to block funding of sanctuary cities. His denying of these cities’ federal funding was the result of their refusal to cooperate with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers. This order was challenged by District Judge William H. Orrick of San Francisco, California, in February of that year. It was later permanently blocked.

“A law takes huge acts of legislation to be overturned, and with an executive order, all a judge has to do is say, ‘No, that’s not constitutional,’” Davis said. “They’re so volatile. [Trump] has absolutely no power whatsoever to really, truly make them stand.”

This is also not the first instance in which birthright citizenship has been questioned. In the late 1800s after the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act which barred Chinese laborers from emigrating to the U.S., immigrants from Asia used the courts system to protect themselves. The Supreme Court ruled that those born within the boundaries of the United States had rights to citizenship that could not be dismissed. This decision validated birthright citizenship in a scenario that mirrors that of this nation.

“This is not the first time this has been challenged,” Zach said. “During another time of mass immigration into the United States, there was a discussion about making sure the 14th Amendment didn’t protect people who were having children illegally in this country.”

Technically, an executive order is not a law, meaning it is weakened in its degree of enforcement. The order cannot receive federal funding. In most cases, executive orders are used to urge Congress into making decisions on laws/issues that have yet to be decided on.

“The president usually issues an executive order in place of legislation that they feel is not getting passed by Congress, and it’s kind of a bully move to try to push Congress into passing it,” Davis said. “It’s like a last ditch effort by a president to try to push Congress into creating some piece of legislation they think should be immediately addressed, but it’s not as dictatorial as people make it sound. Executive orders have very little power of enforcement.”

The proposal of this executive order can be viewed as a claim with more bark than bite. In any circumstance, it has spurred fear and concern for illegal immigrants and their anchor babies. The topic of immigration, legal and illegal, is one that has been discussed and argued for generations without an enduring solution. Whether Trump’s executive order comes to pass or is just another fleeting comment by the president, it has once again highlighted the pressing issue that is immigration.

“We failed to implement policies or create policies that would fix this problem long before. With 30-plus million undocumented immigrants in the United States of America, those people are in limbo for two reasons,” Davis said. “By now, they should have created a system of legality, but they keep putting Band-Aids over the issue. Then you have these knee-jerk reactions, like you’re having now, where people think of these simplistic policies to solve gigantic complex problems.”

Through her eyes

Illegal immigrant remains intent on succeeding in America

She didn’t ask for this, to be a target in the only country she’s ever come to know, to be hidden away, detained by the fears surrounding her. She was only a child, unaware of what was in store for her future. Yet she grew up blaming herself for what she wasn’t able to control or able to change. It was her fault and this country didn’t want her, a statement she believed in for many years.

Each day families are immigrating to the United States, whether by transportation or by crossing the Mexican-American border to escape poverty, violence and other difficult situations in their countries. Many see it as a new beginning, a fresh start to accomplish their dreams and aspirations. Yet few understand the harsh reality of how difficult the transition from an illegal immigrant to an American citizen can be.

“I was born in Mexico, and I really didn’t have a choice or [awareness] of what was going on because I was three at the time,” Maria* said. “I was under false identification papers from another child, and my mom came the hard way through the river and the safehouses. I really have no memory of what I went through, but it was hard because I didn’t know any English. I didn’t have anybody to talk to, and my mom was my only companion.”

Maria didn’t understand the impact of being an illegal immigrant until she reached high school.

“Nothing had gotten complicated while in middle school,” Maria said. “I used to think, ‘Oh well, it hasn’t affected me yet.’ It hadn’t hit me until I got to high school. I was like, ‘wait, I need a social security number, I need my driver’s license. How am I going to go to college? How am I going to get a job? How am I going to get there to be someone?”

While in high school, Maria began to formulate her goals for the future.

“It has made me desire to be someone,” Maria said. “It upsets me whenever I meet people that are citizens and have all of these opportunities, but they don’t want to do anything. I don’t want to say that things will be easy just because I think we all have to work our way up and work for the things we want. [Citizenship is] not going to be given in our hands.”

The obstacles she’s had to endure has left her with mixed emotions, as well as the struggles she’s had to watch her mother surpass. Yet even though they started from nothing, they’re slowly making their way up.

“It’s hard because I see my mom struggling with the financial state we’re in,” Maria said. “I wish that people wouldn’t judge others for not having a piece of paper because deep down we’re all the same. We want to give something back. My mother has done nothing but give pieces of herself to us. It’s not fair because she’s had to clean houses for other people, and I’m not saying that is not a decent job. It is because it’s honorable, but she could have done much more. We had to start from the bottom.”

The process of looking for people and applying for citizenship has not been simple and few options have been offered to her in order for her to accomplish the next steps. New issues have arisen because her parents aren’t citizens as well, which only makes the process more difficult.

“The process starts with trying to find the right people and who to trust,” Maria said. “If information of not being a citizen gets into the wrong hands, it can definitely go wrong in many different ways. Fortunately, my mother and I have come across people who accept it.”

While Maria does have options for seeking citizenship, they are costly and none are easy.

“It’s complicated because we need to gather up money because the processes aren’t just going to be free,” Maria said. “The options that my mother has given [are] that I can either wait until I’m old enough and get married to a citizen or get adopted into my aunt’s family that actually has papers. My mom is so selfless. She has thought of giving me up for adoption to a completely different person just so that I can have a better life.”

Circumstances involving her age and name have also proven to be significant elements in the process, but her family is doing everything possible to acheive the overall goal.

“I’ve started the process, but since my dad has never been in my life, I’ve never used his last name. I stuck with my mom’s,” Maria said. “If I tried filling out any papers they’d ask for [proof] that I’ve been here long enough. Since all of my school records are just my first name, my last name, and not exactly as it says on my birth certificate, they’re not going to think it’s the same person.”

One of the main points she can’t emphasize enough is that not all immigrants come here to ruin the nation but to excel alongside it.

“It just frustrates me because that’s not the intention that most of these Hispanics have as they’re crossing the border. They only want something better because they’re running away from violence and from no opportunities. They’re just trying to have a better life, literally, the typical line of the American dream, but it’s more than just that.”

Maria said it’s about more than having money or a better job.

“It’s about becoming a better person and getting away from the bad influences that are around them,” Maria said. “We all don’t have the same opportunities but that doesn’t mean we can’t all reach the finish line. Some of us have advantages while others have to work harder to get there.”

Despite all the obstacles, Maria remains determined to find success.

“I’m not going to let my status stop me from being someone or from trying to go to school. I have dreams, and I intend to fulfill them. I’m not going to let a piece of paper stop me.”

*name has been changed

Venezuela’s exodus

Family seeks refuge from war-torn country

People in the streets protest for peace and liberty from an oppressive government in Venezuela. The country has faced an economic crisis and rampant inflation, leaving many of its citizens in poverty.

One family in the midst of a failing nation. Owners of the English Academy, Centro ISI, yet they’re as equally impoverished as everyone else. Starvation is a word known too well by many. Limiting rations of food is normal for their family, and hunger is something they face each day. Outside their home, outbursts of chaos and havoc keep them alert throughout the day. At any given moment, they can be robbed, kidnapped, even murdered. They have to do something to save their family.

Venezuela has been plagued by hyperinflation, lack of food, power cuts and lack of medicine. This has led many to flee the country, and seniors Santiago and Samuel Silva are no exception.

After Nicolas Maduro won the special election of 2013, riots and military intervention created a violent environment for Venezuelan citizens. The truth is that Venezuela is one of many nations under these conditions. Resilient individuals and families everywhere search for ways to escape hardships for a better future.

“They came into the government saying that they were ‘socialist,’ and then they turned into a communist government. In a socialist government, the goal is to make everyone equal right? They accomplished that, but everyone should have enough money,” Samuel said. “Instead, they made us all poor. The government is basically a dictatorship because all the powers converge into the president, which is Nicolas Maduro.”

Venezuelans are suffering great costs and are barely managing. The average Venezuelan lost 19 pounds, and 50 percent of Venezuelans lived in poverty.

“We are an oil rich country, but all the money that the country makes is taken by the government, and we’re left without money. We do not earn enough in order to buy food, and everything is expensive due to the inflation,” Samuel said. “Getting food is difficult for everyone, from the richest to the poorest. It’s a struggle to get medicine as well. We were doing what was necessary in order to survive.”

Venezuela’s economic crisis began under the leadership of President Hugo Chavez in 2010 and has continued to worsen and collapse over time. With the exchange of the Venezuelan monetary system, buying something as simple as a chicken could take a whole month with the average Venezuelan pay.

“They changed the currency in Venezuela; now it is Sovereign Bolivar. For example, 5 million Bolivars would equal $1 in the United States, so people could work for a whole month and gain 300,000 Bolivars which wouldn’t even equal half the amount of a full dollar,” Santiago said. “People would travel to Columbia, which is right beside Venezuela, to buy Colombian money because Venezuelan money doesn’t work.”

Money is not the only problem. Food markets and stores are usually completely empty, containing only a scarce number of items. Even if families somehow obtain enough money to purchase a meal, there is no guarantee that they will come across one.

“There’s nothing in the supermarkets, absolutely nothing. Sometimes you’ll find pasta, rice, and very rarely, will you find meat. There’s no variety. It’s always the same. There’s water, but no refreshments,” Samuel said. “There were foods that were expired, so it was really difficult finding food that wouldn’t make us sick. It was very dangerous to get sick in Venezuela because there is very little medical help.”

The lack of food, medicine and constant violence within the nation and abundance of impoverished individuals led many Venezuelans to take to the streets and protest.

“The last time that there were protests was in 2017. It started because we could not take it anymore. People were slowly getting fed up with it until the country exploded. Everyone came out to protest. Of course when the people start protesting, the government gets scared because they can overthrow them, so they sent the military to kill us,” Samuel said. “The protests were practically a war between the military and the protesters — them with guns and us with whatever we can find.”

Violence does not only take place in the streets, but within the homes and workspaces of average Venezuelans. For the Silva family, many instances of danger and violence occurred on a daily basis.

“The government and the protestors would always shoot in front of our house and release gas bombs. There was a lot of robbery and burglary,” Santiago said. “I remember one time I was at my dad’s institution doing homework, and when I looked up, these men had come in with guns taking everything that we owned.”

Because of these recurring events, the Silva family decided to take action to save their family. Not everyone has the same ease immigrating to the United States and consider themselves blessed.

“My dad came to the United States last year to get a job. When he came back [to Venezuela], he had told us that he got a job in Texarkana at Nash Elementary. They had told him that he needed a visa, so when he came back, he got it. Once he got his visa, he returned to the United States on Nov. 16,” Samuel said. “We were without him for about three months, but eventually on Feb. 20, 2018, we headed for the United States.”

The Silva family is now prospering in America, living free, safe and better lives.

“It’s a huge relief to be here. Just recently, three states in Venezuela lost power for 10 hours and my friend wrote to me about it. He said there wasn’t any electricity, that everything was a disaster, and he wanted to leave,” Santiago said. “I feel blessed that my parents were able to save us. Although I do miss a lot of things, I have to see the brighter side. The friends and family that one leaves is very difficult, but I have faith that things will get better and that we can go back someday.”

Bilingual schools

Elementary school programs give students advantage of biliterate education

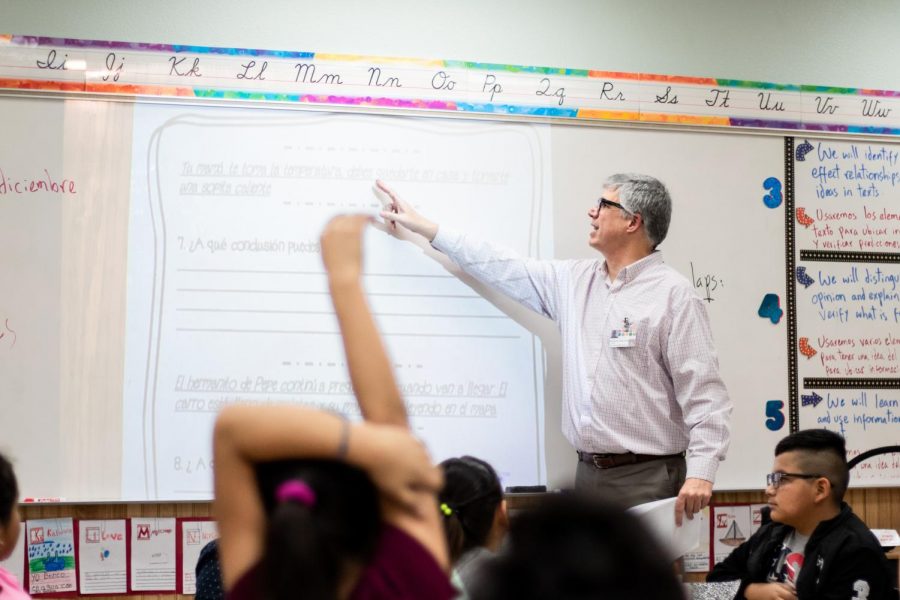

Photo by Holland Rainwater

Students of Nash elementary raise their hands to answer a question on their assignment. Bilingual teacher teaches a class completely in Spanish. Depending on the day, the class alternates between languages that the class will be taught in that day.

Words fumble around the mouths of children as they try to string them together into a sentence. Their tongues twist and turn as they try to pronounce sounds foreign to them. Their thought processes are hindered by their vocabulary and ability to build sentences, and communicating is nearly impossible.

That’s the issue that bilingual programs are aimed to fix: to bridge the gap between the native language and English. Nash Elementary and Highland Park Elementary have bilingual classes in which students are taught in both English and Spanish.

“The bilingual program in TISD began in 2008-2009. At that time, TISD was responding to a growing population, after having 119 district-wide English learners the year before,” Coordinator of Multilingual Education Mindy Basurto said. “Our English learner students were largely Spanish-speaking as they largely are now; therefore, we offered a Spanish bilingual program.”

In terms of teaching this new generation of bilingual students, both elementary schools follow what is known as the Gomez and Gomez Dual Language Enrichment Model.

“It’s designed to where Monday, Wednesday, Friday are Spanish days, and Tuesday and Thursday are English days,” Nash assistant principal Liliana Luna said. “But as far as instruction goes, when you’re in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade, you’re reading and writing is always in Spanish because we want to develop that native language. And then starting in second grade, you get both in English and in Spanish. The kids transition from all Spanish to English really well.”

Along with the teaching method comes the difficulty of attracting qualified teachers to the area.

“It’s been difficult,” Luna said. “Because we’re in less of an urban area, we don’t attract a lot of bilingual professionals. So when we do have an opening, we are required to look outside of our school.”

Luna said they have traveled to the international job fair in Houston seeking applicants.

“Sometimes it is difficult to convince people to come work in small Texarkana,” Luna said. “We have people that will come, but then they realize this is not the type of town that they really were thinking and end up moving.”

Ultimately, they hope that, as the program grows, they will be able to encourage high school students to pursue teaching degrees and return to the district to work.

Although the two elementary schools seem all-encompassing when it comes to the bilingual students, it was not long ago when TISD didn’t have a bilingual program.

“We didn’t start pre-K through fifth [grade]. We just started with pre-K through kindergarten, and then we added second and first grade and so on,” Highland Park principal Jennifer Cross said. “As those kids moved up, we kind of just increased at one year at a time.”

Bilingual education hasn’t escaped controversy. Critics state that since English is the most widely spoken language in the world, there is no need for young students to be burdened with a second language in their education. However, Cross holds a different view.

“I think [being bilingual] is important, and I’m almost envious that I am not bilingual,” Cross said. “And just because they speak a native language doesn’t make them more or less entitled to learn English. So if they can become biliterate, which is having that academic language in Spanish as well as English, they will be three steps ahead of everybody else. It’s awesome.”

Even though many would expect criticism from outside the bilingual community, both school districts face difficulties with educating the parents of the bilingual students as well.

“There’s a little bit of a struggle with the parents in that the parents want that English acquisition quicker than [at the rate] they’re getting it,” Cross said. “But we constantly try to reiterate to parents that it’s important to get that knowledge in your first language, and then it’s going to translate very easily into English.”

Aside from outside criticism, the district faces a bigger problem: class sizes. Forty-two percent of Nash students don’t live in that attendance zone.

“When I first started here eight years ago, we were at 400 and something. Now we’re close to 700,” Luna said. “[There’s a] large population of transfer students who do not live in the area [who] are choosing to come here, and a lot of the transfers are within [the bilingual] program.”

These exceedingly large class sizes have led to many bilingual students from the Highland Park area to be bused to Nash in order to go to school. I

“However, if the student lives across town and there is no space at the closest bilingual campus, we will transport students to the campus that does have space available,” Basurto said.

Bilingual programs have been shown to be effective in creating students who are bilingual, bicultural and biliterate, which is a district goal, Basurto said.

“Reading scores for students who are placed in dual-language bilingual programs far surpass those of students who are in ESL programs, so we strongly encourage families to consider the dual-language bilingual program we provide to our English learners who are Spanish speaking,” Basurto said. “Once a student learns to read in the first language, all of the literacy skills transfer to their second language. A student’s successful literacy acquisition in both their first and second language is directly related to phonological awareness in the native language. This is why we are bound by law and by ethical obligations to provide our students with the best opportunity to help each individual student succeed.”

Due to the large class sizes and the increased need for transportation, the district spends more money on these students, although federal and state funds cover these extra costs.

“Our district receives federal and state funds to help us educate English learners,” Basurto said. “Our state bilingual allotment is a little over $240,000, and our federal Title III funds are a little over $46,000. These funds must be used for specific things that English learners need in order to attain English proficiency and to access the curriculum.”

Despite any difficulties faced by both schools, they still hold firm beliefs that they are helping these children and giving them an advantage. Students who are in the bilingual program should graduate not only speaking the language but being able to read it and write it.

“Depending on what career field they go into, being biliterate is definitely going to give them an advantage,” Luna said. “It has been an advantage for me. I feel like it has helped me advance within my career because I am bilingual, or biliterate, and TISD offers what they call a bilingual stipend, that’s additional money for employees who are biliterate.”

When it comes to getting a job, being bilingual may put one applicant over another.

“If you have the same level of education, same level of experience, but one [applicant] is bilingual and one isn’t, it’s definitely going to be an advantage,” Basurto said. “So that, I believe, is a huge benefit.”