The cards you’re dealt

March 5, 2019

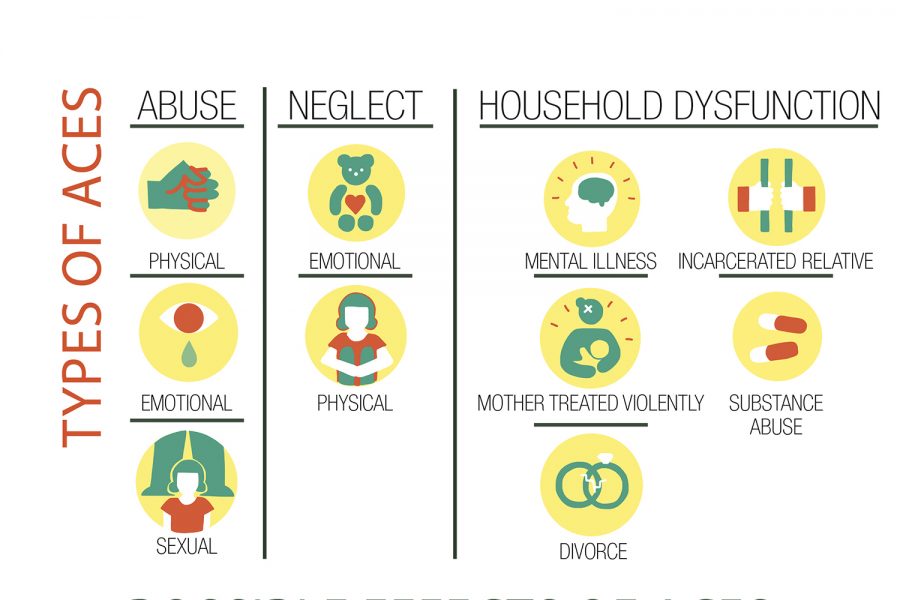

Childhood traumas, also known as Adverse Childhood Experiences, have been tied to heart disease, diabetes, alcoholism, cancer and other medical conditions. These are the cards we’re often dealt, but how we choose to play our hand is entirely up to us.

Graphic by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Adverse childhood experiences

Childhood events can shape health issues later on in life

Adverse Childhood Experiences are traumatic or stressful events that occur before the age of 18. ACEs include abuse, neglect or household dysfunction. An ACE could be identified as a multitude of events, such as divorce, domestic violence, emotional neglect or sexual abuse.

ACEs trigger toxic stress, which activates the brain’s fight- or-flight stress release system (FFSR). This is a two-part system. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) triggers the activation, and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) returns the body to its normal state. This response is used to protect people from immediate physical danger, which then results in emotional stress, but more recently, this stress has been triggered by memories of negative experiences. The repetition of the FFSR system causes two types of life-long consequences.

Physical Health Consequences:

Chronic activation of the FFSR system can result in unhealthy eating habits and sleeping patterns, racing heartbeats, back pain and even the shut down of body systems. Consistent shutting down of the digestive system can cause migraines, hair loss, skin rashes and dizziness.

Mental Health Consequences:

Tolls on mental health can appear in the form of depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, feelings of hopelessness, difficulty concentrating, or the need to be in control.

There are four common coping skills that respond to the FFSR system:

(Fight) Yelling, crying or physically lashing out. This is more common with children who do not understand how to express their emotions, resulting in the need to fight.

(Freeze) Shutting down when facing conflict. This skill is learned in childhood and teenage years. Instead of reacting or engaging, people freeze because it has kept them safe.

(Appease) Consistent concern for others feelings and the need to appease is another coping skill. This is used in attempts to prevent conflict.

(Deflect) Trying to manipulate and blame others for one’s guilt is considered denial, deflecting the effects of the FFSR system.

It starts at home

Impact from ACEs can be overcome

Home environments built on Adverse Childhood Experiences in which children grow up have lifelong implications.

The earliest stages of development occur during one’s childhood, so any experiences during that time can have a substantial impact on lifelong physical and mental health, especially if they are negative. Harmful effects on the foundation of brain structure can occur, which can result in unhealthy coping behaviors, low-life potential and even death.

“Childhood experiences provide the building blocks for future learning, behavior and health, which provide the brain with a sturdy foundation for future development,” said Melissa Merrick, senior epidemiologist for the Center of Disease Control. “Early adverse experiences like abuse, neglect or unhealthy relationships can impede the progress of a strong foundation, affecting brain architecture and optimal development. While some degree of adversity is a normal and essential part of human development, exposure to frequent and prolonged adversity can result in a toxic stress response.”

Toxic stress responses can cause disruptions in the development of bodily organ systems as well, which can result in an increase in health issues and social consequences. To prevent these types of problems, one can start from the core of the issue: how children are raised and treated. Through the CDC’s program, this goal can be achieved.

“CDC promotes lifelong health and well-being through the Essentials for Childhood Framework, ensuring safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments for all children. The Essentials for Childhood Framework proposes strategies communities can consider to promote relationships and environments that help children grow up to be healthy and productive citizens so that they, in turn, can build stronger and safer families and communities for their children,” Merrick said. “Safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments may stop ACEs before they even happen by building a strong foundation of healthy relationships and environments through which children can thrive and reach their full health and life potential.”

The relationships built with children and adolescents are only a small factor of the solution. The environment they grow up in also has some effect, and because of this, ACE advocates try their best to provide adults with information on how to improve their living situations.

“Safe, stable, nurturing environments play a large role in preventing ACEs by creating a context and atmosphere that allows families to share quality time together, to discuss and resolve conflicts, and to provide emotional support to one another. Community and organizational decision-makers — both in the private and public sector — also play an important part by developing policies that create conditions and resources that support safe, stable, nurturing environments that benefit children and families,” Merrick said. “CDC’s technical package for preventing child abuse and neglect identifies a number of strategies to help states and communities prioritize prevention activities based on the best available evidence. These strategies range from a focus on individuals, families and relationships to broader community and societal change.”

ACEs should not overcome an individual’s ability to live a free and happy life. Everyone experiences a form of adversity, but the way it is handled and how one recovers is what is important.

“It is important to remember that both positive and negative childhood experiences can have impacts on health and well-being,” Merrick said. “If someone has ACEs, this does not mean they will definitely experience health or social impacts. That’s good news, since we know that the majority of people have experienced some form of childhood adversity. But everyone responds differently to ACEs, and many of us have positive experiences in childhood and youth that can greatly offset and outweigh our negative experiences.”

The answer changed everything

Childhood experiences affect teacher later in life

Photo by Oren Smith

She was only a child, yet she knew what the empty bottles would cause. She knew what was happening was wrong, but she had no way of making them stop. It was their job to nurture her, but that did not seem to be their main priority. Her best option was to make sure that no one could tell something was wrong even if it was hard going through everything by herself. Little did she know that the experiences from her childhood would later impact her adulthood.

Math teacher Katie Diaz suffered many traumas during her childhood years, one of those being the extensive substance abuse of her parents. At school, Diaz seemed normal, but the story was completely different at home.

“I was very quiet, always did really well in school. I wasn’t involved in much. You wouldn’t have known that my parents had an abuse problem with alcohol,” Diaz said. “My parents did everything they thought was right for me. They were there to give me food and shelter, but kids need a lot more. Kids need nurturing. I was always overweight as a child and that was something I was criticized on a lot at home. I think that’s why on the school end of it everything seemed fine because I was striving to at least do that right.”

As an adult, Diaz was diagnosed with cancer multiple times. Her doctors were unable to provide answers for her condition, so Diaz did research of her own. Diaz came across the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, which helped her seek closure.

“I had to start chemo, and I was mad because I didn’t know why this was happening. I had genetic testing done to see if it was hereditary. It wasn’t anything. There was no explanation to why I had the cancers that I had. I was mad for quite a long time, especially after the third cancer. The third cancer took my ability to have children of my own,” Diaz said. “That’s why I wanted to spread the news about the ACEs test.”

The ACEs study asks questions about one’s childhood and the traumas that one may have experienced. Through this test, Diaz learned that her parents’ substance abuse was a component of her infertility.

“ACEs stands for Adverse Childhood Experiences, but it isn’t really well known from what I’ve witnessed. It’s basically a test to see what childhood experiences could have effects on you later in life. They ask questions about anything traumatizing that happened to you, like being raped as a child, things like that,” Diaz said. “You don’t have to go into detail about what’s going on; it’s just yes or no and then the scoring. Their statistics are based on your score.”

Although the test provides statistics and details about what may happen in the future or what effects the past has had, it is not always guaranteed. In Diaz’s case, following in the footsteps of her parents was something she could control but the health effects were not.

“When I was younger, since I was around [substance abuse], it made me not want to do it,” Diaz said. “I’ve broken out of the statistics for that part.”

When Diaz took the ACEs test, she scored an eight, a high score.

“I felt guilty. I felt at fault for being sick, and my husband was stuck with somebody who couldn’t give him another child,” Diaz said. “A lot of weight was lifted off of me when I found out about ACEs. It gives reassurance that a lot of things aren’t in your control. I believe that I’ve been taken care of, and by the grace of God, I’m still here.”

The ACEs exam not only provides an explanation for the score received, but outlets and the right support for the individual as well. Diaz views this exam as an opportunity for counselors and teachers to further help students understand and cope with their situation.

“This test helps a lot for counselors in schools if they are aware of this test. They can relate that information back to teachers, parents and understand the effects that a kid can have. Later, when a child can understand what the score means, they can understand that they’re not defined by what happened to them,” Diaz said. “Even though there are statistics out there, there’s also answers and support groups. When you talk about somebody talking to a therapist or psychiatrist, a lot of people think that that person is crazy, but it’s not that. Some people really need that to be able to work through those problems. It’s OK to talk about what’s happened to them, it’s OK to work through that with somebody else.”

Diaz takes advantage of the knowledge she has gained from the exam and her life experiences to make sure that her students can trust and feel comfortable to speak out, whether that be with her or any other adult.

“When you walk in the room, we know your name, we know your ID, we know what kind of classes you had the year before, but we don’t know anything about what you’ve been through,” Diaz said. “I personally try to get to know all my kiddos as much as I can.”

Diaz said her door is always open for students to come talk.

“If you have at least one person, even in that traumatic childhood, that you can go to, your chances of of having problems later on go down,” Diaz said. “All it takes is that one person that knows what you’re going through to understand and help you through it.”

Diaz encourages any student who may be going through a hardship to speak up and accept help because even the smallest piece of advice or a single suggestion can change the direction of a person’s future.

“Like I said, for a student like me, you never would have known [anything was wrong] because I didn’t come out and say it,” Diaz said. “So if you have a teacher that reaches out to you, take them seriously. It can be your parents, your teachers, or any other adult in your life. I’ve learned here at Texas High, so many teachers would do anything for their kiddos, and I’m one of them. I love my kiddos so much.”

Through difficult times, Diaz reflects back on one of her favorite memories to surpass feelings of anxiety and hopelessness. She keeps in mind that even though she had it rough growing up, she’s still here and getting better each day.

“Last summer, we took a trip to Mexico. We [visited] a beach down there. This was after I’d finished chemo in December, and I was starting to get my strength back. I was starting to get a pretty good length of hair back to where I wasn’t completely bald. I felt like my body was recuperating from being torn apart from the inside out,” Diaz said. “I kind of walked off from my family and went down to the water and just stood there and looked across the ocean. I let the tide come in as my feet sunk into the sand. The waves were crashing up and the wind was blowing, and it was a moment where I felt peace. I had made it through one of the most difficult times, and I was still alive.”