The age of accessible learning

November 18, 2018

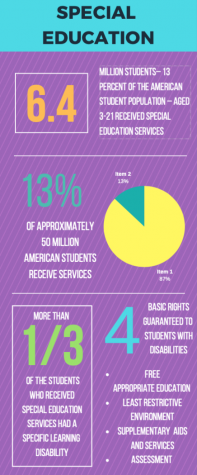

Efforts to create an inclusive environment for special education and those with physical disabilities creates a better educational setting for all. These stories give a closer look into the lives of special population students, teachers and parents.

Opening a closed door

A look into the reality of a special education class

Room 49, a composition of rooms that quarters several classes that serve the special populations of Texas High. Within its boundaries, a self-contained class, vocational and life skills classes, and speech pathology offices can be found.

For students who have no reason to travel to Room 49, the distinctions between general education and special education may go unnoticed.

“We obviously have to differentiate a little bit more. I don’t do any academic courses, so we do all hands-on tasks in our classroom. A normal general ed teacher is going to be teaching to their subject while mine is all life application,” special education teacher Heather Boutrouss said. “Everything I do in my classroom is differentiated. For everybody, we mold; we modify.”

The content of the instruction is also different.

“We spend a big majority of the morning learning how to write and learning the letters and numbers, just overall, many things people take for granted,” special education teacher Samantha Autrey said.

A general education classroom normally follows this outline: lesson, assignment, quiz, then test. Most of these tasks will be done alone. In a self-contained classroom, most assignments will be completed in groups and incorporate a tangible component.

“Special Education is more hands-on where general ed would be more paper and writing,” Autrey said. “A test is more of an observation. It’s not necessarily gonna be so many questions or a review over this. It’s collected over everyday.”

Due to the students’ distinctive differences, there cannot be a one-size-fits all classroom, but one in which modifications are made for each student in order to best serve them and enhance their take away from the class.

“Every student has different accommodations in my classroom. It could be anything like popsicle sticks on pages because one is paralyzed on one side, so he can turn a book page. It can be enlarged [text] because of a vision disability,” Autrey said. “It can be sensory issues where they can’t work with certain textures, so you have to change it completely. It just depends on every single student. Everyone is accommodated differently.”

The role of a special education teacher is more complex than that of a general education teacher because they are responsible for more than just instruction and examination.

“You’re not just a teacher. You’re more of a caregiver, too,” Autrey said. “Where other students rely on the nurse, we are also that person.”

The overall goal for most teachers is to prepare their students to go to college or directly join the workforce, but this does not apply to the students of Boutrouss or Autrey. In terms of Room 49 students, their aspirations seem simple but are, in fact, just as formidable.

“Our long-term goal is to be able to have these students able to cook for themselves using a microwave, understand how to clean, how to wash dishes, how to wash clothes, just those application skills,” Boutrouss said. “For me, it’s just getting them ready for life. Being able to teach a student to function in the world and be successful is my biggest goal for my students”

Despite their differences, the students of Room 49 are still part of the school’s student population before they are a part of special populations, and that needs to be emphasized when they’re outside the classroom.

“If you see us in the hallway, stop and say hi. My guys love to talk to people. They love to meet new people, say hi, and give high fives. Don’t be afraid of that. It’s a good interaction,” Bouttrouss said. “It’s so important for our students to have that interaction because they are going out into society and have to understand how to function with people in a regular setting. Don’t be afraid of that interaction. Embrace it.”

A special population

Students reveal there’s more to program than meets the eye

Photo by Rivers Edwards

Senior Auquasia Richard works on a painting. Richard created several paintings for her art class to express her creativity.

Special education. Those two words shouldn’t be so jarring, shouldn’t carry an undertone of discomfort when spoken aloud. Yet somehow, the words special education carry their own aura, one of mystery and whispers, as if everyone knows what the secret is, but no one’s brave enough to say anything. Afraid of violating the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act or being politically incorrect, people opt for silence instead, as if ignoring an entire population isn’t just as painful.

Students with special needs are just that— students. They go to class, make grades, go to lunch and have after school hobbies. They are unique and diverse, and lumping all special needs students under one label— or one room number— is fair to no one. Everyone has a story, so why hasn’t this one been told?

Senior Auquasia Richard is 17 years old. She loves painting, swimming and getting pedicures with her mom, Shasta Richard. She was also diagnosed with sensory integration disorder, autism and ADHD when she was 3 years old.

“I started noticing different signs that she wasn’t catching on and she was behind her peers, so we got her into Opportunities and started doing therapy to decrease some of those obstacles she struggles with,” Richard said. “Most of the time she is a loner in everything. She is kind of standoffish until you make her comfortable with her being around you, but after that, she’s like this butterfly. She has come a long way since she began high school, a very long way.”

Though Auquasia’s story seems unconventional, the way the proud mother describes her daughter never changes.

“I wanted to expand to see what it is that she likes,” Richard said. “Then they put her in art, and she loves painting. She just loves everything about painting. She just kinda doodles [all the time], and she just takes her time where somebody else might do it a little faster than her. She’s also been swimming for four years, so she’s really good at swimming. She swims like a mermaid.”

Unfortunately, not everyone shares the admiration Shasta has for her daughter. Many kids and adults alike seem to exclude students with special needs.

“I feel that a lot of times a child with special needs is shunned,” Richard said. “[People think] ‘I don’t want to deal with them, it’s too much of a problem. They may cause embarrassment or they don’t know how to act.’ There’s just a lot of obstacles and barriers that they go through.”

Though Richard fully supports her daughter in all of her endeavors, she is keenly aware of the stigma that surrounds special needs students. She, however, isn’t the only person to make note of this issue.

Ashley Alexander, a 2003 Texas High graduate, has also felt the effects of stigmatization due to being a part of special needs.

“I feel that at times I was looked down by my peers for having a learning disability,” Alexander said. “The best part of having an IEP plan was when I needed extra help or more time, I was able to have that. The worst part of having an IEP plan was some of my teachers just got to know my plan versus me as student.”

The scope of what special education is is quite expansive, but it is often viewed through a narrow lens. The role it plays in the lives of those with disabilities is different to each individual. Every person faces different hardships and triumphs. This is true for all people, and 2016 Texas High graduate Mackenzie Tellez is no exception. As a child, Tellez was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and was a part of the special education program all throughout high school.

“Overall, the Texas High special education program was amazing,” said Amy Tellez, Mackenzie’s mother and special needs diagnostician. “The teachers encouraged her and very few ever told her she couldn’t do something.”

One would think that it is the disability itself that causes problems, but oftentimes is the way in which the disability is handled from an educational standpoint.

“Right before the STAAR test in Mackenzie’s ninth or tenth grade year, her accommodations were taken away without us knowing,” Tellez said. “She wasn’t going to have her tests read to her when she struggled with comprehension. We met at the end of the year requested an evaluation to see exactly where everything fell, and the evaluation revealed that Mackenzie had an intellectual disability, not a specific learning disability, and was able to receive all of her accommodations.”

A solid support system in schools is vital to all students, especially those with special needs.

“Special education is an individualized instruction that is based on the student’s individual need. Not everyone learns the same way on any given day, that includes all students,” Tellez said. “Special education is designed to help those students who continue to struggle to learn and cannot retain the information as typically developing peers do.”

The parents of special needs children find themselves in a unique position. They must balance their instinct to protect their children from criticism with their desire to push them to be more active in society.

“I do believe it is a two-fold process as parents. You have to migrate your kids into the community so that they can be more aware of what’s going on around them,” Richard said. “Sometimes as special needs parents, we kind of shelter them because we don’t want them to get hurt or we don’t want to anyone to make fun of them, but at the same time, you have to get them out there.”

The exclusion of special needs students is a complicated issue. As a society, we must ensure we are doing our part in taking a step back from the human instinct of stereotyping and moving forward in a way that includes everyone.

“I am a parent and I want my child to be included. Don’t leave them behind,” Richard said. “I just want my child to be treated equally. I’m not asking for any special favors for Auquasia. Treat her like you would treat anybody else, but at the same time, do consider where her level is. Just don’t say I can’t be bothered.”

While being the parent of a child with disabilities comes with its hardships, Richard believes the reward is far greater. Every person has something to offer, and individuals with special needs are no exception.

“There is a lot that goes into being a parent, and Auquasia has taught me so much. [She taught me to] just see people for who they are. I never thought that I would be the parent of a special needs child,” Richard said. “Auquasia has taught me to not just look at the outside, but look at the inside. Don’t look at my disability. Look at my ability to get things done.”

Fear causes silence, and silence causes fear. This paradox creates the culture of being afraid to talk about special needs, and it can only be broken when parents are brave enough to speak up.

“I’m not scared to talk about it,” Richard said. “The reason why I’m not scared to talk about it is because I feel like if it reaches one person, if it reaches one parent, I feel like we’ve accomplished something. As parents, we don’t want our children to be labeled. We don’t want them to be scared of the other kids or that there’s going to be some type of ridicule. For me it’s more like I want [special needs students] to know that they have a voice. I’m an advocate for my daughter. It’s never about me, it’s always about her, what I can do to make it better.”

And though there has been progress made by these involved parents and dedicated teachers in past years, there is still a long way to go to reach equality.

“My prayer is that Texarkana Independent School District works to create a pathway program and policy that shows inclusivity to all student populations, especially those who tend to be marginalized due to mental, physical or social challenges,” Richard said. “I have yet seen a program designed to help those students who fall under the special education umbrella develop skills to become successful in the real world. Remember the student is only going to be as strong as the foundation it is built upon.”

Collaboration for education

Co-teaching improves inclusion among students, special education

Photo by Bailey Groom

When it comes to special education, students in need of instructional aid often struggle in typical scholastic settings. From social constraints to personal rates of comprehension, the attention they require is often a task much too formidable for one teacher alone to handle. What these students need is similar to what is instilled within any corresponding system of governance: a division of attention–a special approach.

Special education is a distinct experience for each student involved, whether it be physically or psychologically. The resulting sentiment can be one of isolation and confinement, where alienation abounds as a result of basic necessity. Special education blurs the lines between a school with special-education services and that of one which offers a normal, teenage experience for all students, despite special circumstances. Collaborative teaching is a weapon designed to sever this sense of detachment between students.

“Collaborative teaching allows those students that would typically not be in a general-ed class to have the opportunity to not only learn academically, but socially and emotionally,” special education department chair Christie Alcorn said. “They have the opportunity to engage with students that they typically may not even come into contact with.”

In 2014, Texarkana Independent School District introduced collaborative teaching in an effort to provide what the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) coined as a “least restrictive environment (LRE)”. With this transition came the unconventional implementation of two teachers in a class. For instructors like Alcorn, this method has accrued significant results.

“I have been in the classroom for 16 years now, and I wanted to become a collaborative teacher because I could see the benefits for all students,” Alcorn said. “Students who have typically been in a more restrictive environment are now able to come out with their peers and have the opportunity to engage and be challenged in the classroom.”

The decision to collaborate was not an easy choice for every teacher. Ashleigh Bridges, an English teacher who is a newer member of the English department, was hesitant of the idea of professional teamwork to this magnitude. After all, cooperation in the educational field is understandably hard to contrive, as both teachers would need to harness a respectable level of consistent interaction with each other as well as students in order to promote a smooth course-flow.

“Initially, [becoming a collaborative teacher] wasn’t by choice. And, you know, with [Mrs. Alcorn’s] 16 years and my few years, we were kind of worried that we would clash, [but] it just works out really well,” Bridges said. “Once they explained what it meant, it reminded me of my student teaching, when I actually collaborated with a teacher and we split the class. I believe it is important because the kids truly get the one-on-one [experience].”

Collaborative teaching is not only beneficial for the quality of student education but also for that of participating faculty. For two educators working together, the classroom is a piece of art in which both utilize their individual skills to produce astounding results. Where one layer may have left thin in an artwork, the next manages to smooth out these blemishes.

“For me and Mrs. Alcorn, things that I can’t explain well, she can explain well – or vice versa,” Bridges said. “I may have a positive relationship with the kid, but the kid may not like her. And so it really helps to have the two bodies in the room–where I can do one thing when she does another–and they all get what they need.”

With their first year out the door, Alcorn and Bridges fine-tuned their collaborative strategies over the summer in preparation for the impending semesters. One tactic they exercise is that of a shifting arrangement, in which they break the class into two groups–one for each teacher.

“Just because [Mrs. Alcorn] is a special ed teacher and I’m the general ed teacher doesn’t mean that she just works with special ed and I just work with general ed,” Bridges said. “When we split, she will take kids that aren’t special ed, 504 and I’ll have some, too. It just shows them that we’re both the head of this classroom. It’s not me with her helping, and it’s not her with me helping. We both run this place.”

Overall, co-teaching within classrooms offers an opportunity for students within the special education program to enhance their academic potential. According to a 2007 research experiment conducted by Roger Goddard and colleagues, there was an increase in the achievement rates of students receiving the collaborative method. Involving special ed. students in the the collaborative process, which includes an increased rate and thoroughness, resulted in an improvement in their math and science scores. Through teamwork and certain sacrifices, these collaborative teachers actively apply their skills in coordination and management to foster the success of their pupils.

“Students are not singled out, especially the students that are in the collaborative classrooms,” Alcorn said. “They are grouped with their peers. You may have two groups [with] the special ed kids just mixed in with everyone else, and so I may teach one group and Ms. Bridges may teach the other group. We plan our lessons, we grade, we collaborate, and we decide what’s best for everyone.”