My invisible uncle

Junior reflects on losing uncle in 9/11

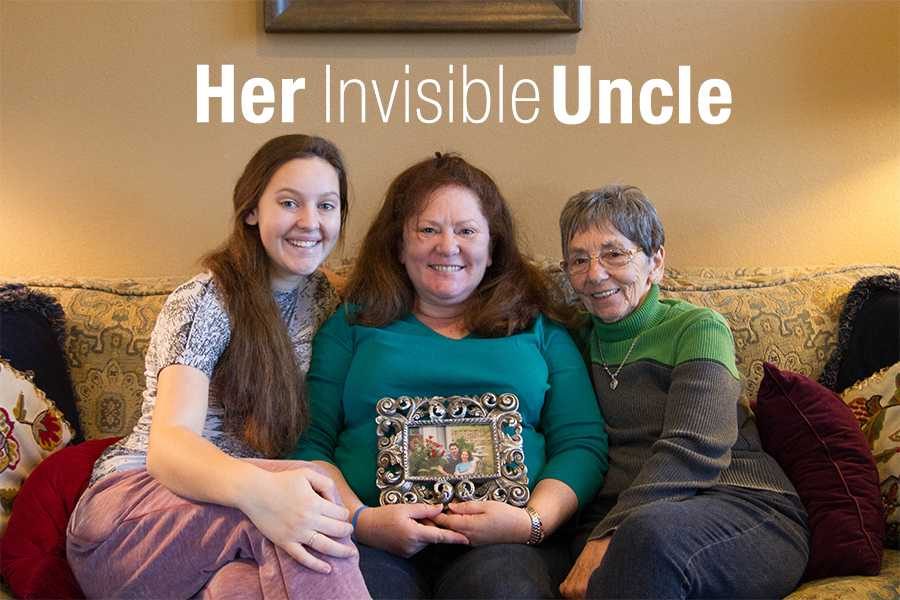

Photo by Brianna O’Shaughnessy

Leah Crenshaw, Mary Kaye Crenshaw (mother) and Claire Taylor (grandmother) hold a picture of Leah’s uncle.

Like most high school kids now, I don’t remember much from 2001. I don’t remember the first Harry Potter movie premiering. I don’t remember my first few days of K4 classes at St. James Day School. I don’t remember my uncle, Michael Morgan Taylor, stock trader for Cantor Fitzgerald on the 104th floor of the North Tower at the World Trade Center.

I don’t remember much about September 11, 2001.

I don’t remember the funeral service. I don’t remember seeing my grandfather cry for the first time. I don’t remember the small ornate box my entire uncle fit into. I don’t remember the stone-faced cemetery workers sealing off his tomb.

I remember the aftermath, though.

I remember lighting candles on the anniversary. I remember my grandmother saying “I don’t cry on that day. I cry on his birthday.”

I remember my mother, teary-eyed, drinking coffee while she describes her dream that night about her brother.

I remember a marble square with flowers and a set of dates, one, his birth, unfamiliar to me, and one, his death, painfully familiar.

I remember the empty place where he should’ve stood in the next family photo.

When I was four, my mother was called into my school by the teacher. She was worried I was depressed. For some reason I wasn’t happy about much of anything. I wasn’t eager to go play with the other kids at recess. I wasn’t happy. My mother tried for words for a few seconds before bursting into tears. In the weeks after Sept. 11, 2001, my mother was grieving, and so, albeit unknowingly, was I.

Later, when I was 12, I was sitting in my social studies class on Sept. 11. There had been a strained, on-the-verge-of-catastrophe sort of silence all morning. In my social studies class, it was similar. No one knew what happened on 9/11, so my teacher decided to play the commemoration videos of the memorial.

I was pulled out of class for crying so hard. The teacher didn’t understand that in an earnest effort to teach his students about a modern American tragedy, he had tripped unknowingly into a minefield of regret and grieving. He didn’t know, and I didn’t know how to tell him.

Those are not the only stories I have about growing up this way.

If you’ve ever been to my house, you know there are four people in my family. I have been blessed to have my father, my mother, my brother and myself. But there is a fifth person in my house you don’t see at first glance. A fifth person stands at the forefront of my mind, a fifth person who, despite being hazy at best in my memory, has a tangible presence with my family everywhere we go. Some losses in my family came so suddenly we didn’t know what to do. This was one of them.

There is a void in the shape of my uncle living in my house. Sometimes, my brother accidentally steps into it. My mother just stares, struck silent until she can form the words “You’re so much like him.” Sometimes I accidentally reveal him, telling a story that makes my mother look into space and say “He loved you so much, even if you don’t remember.”

Now, if you walk into the house on the right day, you can feel him there, my invisible uncle. You can feel the emptiness that engulfs my mother. You can hear his absence at the Thanksgiving dinner table.

You can see the void. The place where he should’ve been, but wasn’t.

My invisible uncle, who lives in my house, lives in my school, lives in the back of my mind, lives in my soul, consists of a confusing swirling void of half-forgotten stories, painful memories and an expectation to live up to his memory. My brother and I both worry sometimes that we won’t.

You can’t see him, you can’t hear him and you can’t touch him, but a part of him is always there: My Invisible Uncle.

Leah made a 5 on the physics AP test, but couldn't figure out how to open the door to Jessica Emerson's car even though it was unlocked. One time, she...

Beyonce. Mermaid. Beyonce-Mermaid. These are words that have been used to describe Brianna. Brianna is currently experiencing her third year of publications...

Noe Monterrosa • Sep 10, 2021 at 8:36 am

I was visiting the memorial for the first time In 2017, and just today I was checking again those old pictures and I saw the name Michael Morgan in one of them. I was curious to know about that person and your article gives me a great idea of how awesome this person was. Thank you for sharing and sorry for your loss

Tom B. • Sep 11, 2016 at 7:06 pm

Thank you for such a beautiful and eloquent story. I was at the 9/11 Memorial die the first time on August 26, 2016. I saw white roses in some of the names and randomly photographed your uncle’s name. It was later that I learned that the roses signified avictim’s birthday. I found myself grieving for someone whom I had never met. The experience of my day at the Memorial was intense and emotional. Living near Manhattan, I had many friends and family affected by the attack, but was fortunate not to have lost anyone close to me. Thank you for sharing your experiences. My condolences to you and your family.

Dee Miller • Mar 5, 2015 at 9:02 am

A lovely and eloquently written article. Well done.