Birthright citizenship

Arguments for and against the 14th Amendment

December 26, 2018

After existing for around 150 years, the 14th Amendment has been called into question by current President Donald Trump. In the wake of this declaration, birthright citizenship is being threatened. Opposing viewpoints regarding the issue present the arguments of differing interpretations of the longstanding amendment.

Rights at birth

The stroke of a pen. In his view, that’s all it takes to end the wave of anchor babies. To end the flow of immigrants into this country, as if a stroke of a pen would erect bigger walls to keep them out. As if that stroke would destroy the hope these parents have for their children.

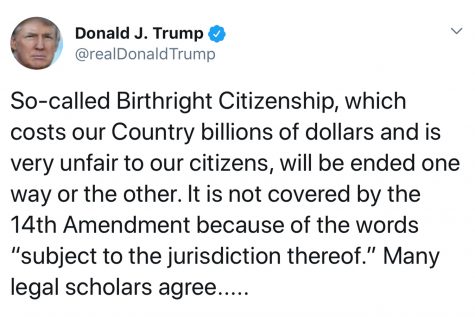

On Oct. 31 President Trump tweeted his sentiments about birthright and his willingness to get rid of it. Trump has been notorious when it comes to his ideas on immigration, but this might be the most far-fetched idea he has publicized since his whole “build-a-wall campaign.”

Eliminating birthright citizenship would do little to solve our immigration problem. Actually, it would have the opposite effect and increase the number of undocumented citizens within the country. The Migration Policy Institute study found that if citizenship were denied to every child with at least one unauthorized parent, the unauthorized population in the U.S. would reach 24 million by 2050. Ultimately, this idea does nothing to advance real immigration reform.

In my case, if my citizenship were denied, I would have been a stateless baby, since Mexico wouldn’t guarantee me citizenship either. I would have had to apply for citizenship, and my parents would have also had to prove that they were citizens, which is not only hard to do, but also expensive. Since Mexico is a developing country, many people within the country have little to nothing to prove that they are, in fact, citizens.

Aside from that, removal of birthright citizenship would go completely against Section One of the 14th Amendment, and in order to overwrite it, there would need to be another amendment ratified, and not an executive order — like Trump wants to do. The problem then arises with the fact that there has not been an amendment ratified since the 27th Amendment in 1992.

In order for an amendment to be ratified, it must first be proposed and approved by two-thirds of the House and the Senate and then sent to the states for a vote. Then, three-fourths of the states must affirm the proposed amendment. The fact that we need not only Congress to agree by a two-thirds majority but also the states to agree by a three-fourths majority makes such a controversial amendment practically impossible to ratify. Arguably, we are in the most polarized time period this country has experienced, and if this amendment were proposed, it would polarize the country even more, leaving us at a standstill.

Most supporters of the removal of the birthright citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment point out the context the amendment was written in. The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868; it was one of main Reconstruction era amendments aimed at giving rights to slaves. Thus, they argue that birthright citizenship was meant only to be applied to slaves within the U.S. and not foreigners entering the country.

What is so ironic is that the main supporters of the removal of birthright citizenship are conservatives, who typically uphold a strict interpretation of the constitution. “All persons born or naturalized in the United States.” And in the philosophy of the average conservative, this is the part that guarantees birthright citizenship regardless of their parents.

All in all, Trump’s insistence on removing the birthright citizenship will end up getting lost in the Supreme Court or Congress — that is, if it even makes it there.

Subject to interpretation

The 14th Amendment has been cited most recently as a response to President Trump’s claims that he can end “birthright citizenship” with an executive order. The 14th Amendment states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.”

The leading argument that tends to resonate most among Trump’s critics is that the 14th Amendment essentially says that any person born in the United States is automatically granted citizenship. However, this would ignore the text and legislative history of the 14th Amendment, which goes to show just how questionable the applicability of this amendment is to children of illegal foreign nationals that are not under the United States’ jurisdiction.

In the infamous Slaughter-House cases of 1872, the Supreme Court ruled that the second segment of the 14th Amendment was intended to exclude “children of ministers, consuls and citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States.” In 1884, Elk vs. Wilkins confirmed the previous ruling when citizenship was denied to an American Indian because he “owed immediate allegiance to” his tribe and not the United States.

Years later in 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act granted citizenship to Native Americans.

This birthright citizenship interpretation of the amendment would be correct if only the first segment existed, which states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States … are citizens of the United States.” Instead, the second segment serves a vital role in directing the way in which this amendment should be interpreted. By adding “ … and subject to the jurisdiction thereof…”, the original author, Senator Jacob Howard, added a key detail that is overlooked by a vast majority of Americans.

According to Senator Howard, these words were intended to have the same meaning as the wording of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which stated “all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power…” are citizens of the United States. By including this one segment, the overall message of this amendment drastically changes.

Many people cite the 14th Amendment as the birthright citizenship amendment and believe that this protects the citizenship status of children who are born on U.S. soil to illegal immigrants. However, a child is only subject to the jurisdiction of the same government as his or her parents and if the child’s parents are illegally in the United States, this must mean that they are citizens elsewhere, thus they hold allegiance or are subject to some other country. Therefore, the child would not be considered a U.S. citizen according to the 14th Amendment.

After careful consideration of the information presented, one could only conclude that the 14th Amendment has been mistakenly interpreted and enforced for many years